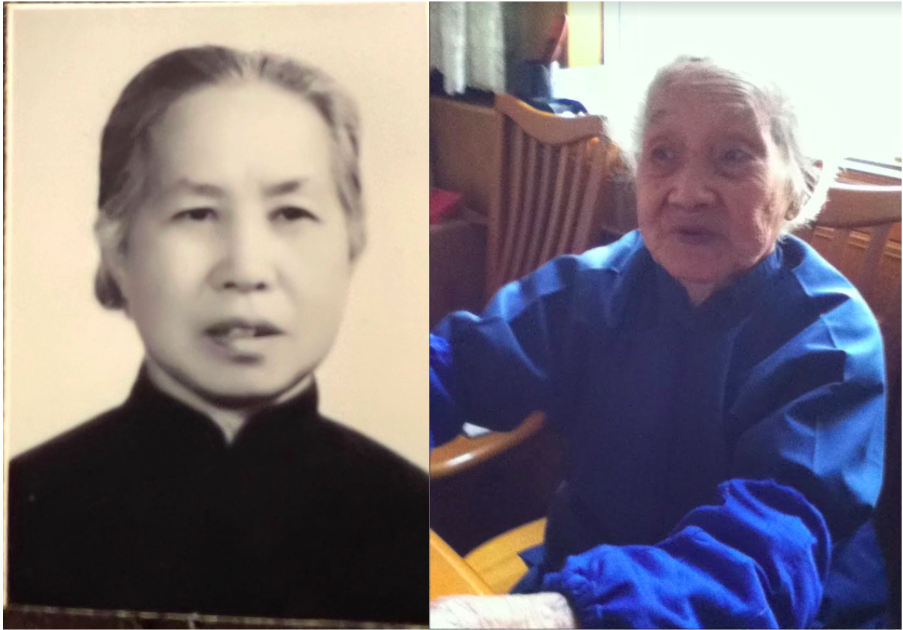

We called her Tai Tai, but her real name was 陆兰英, or Lu Lanying. I only learned that a few weeks ago, nine years after she died. Until a few weeks ago, all I knew was that Tai Tai was my mother’s grandmother and that she lived for 99 years.

What I had yet to learn was that in her life of nearly a century, even when she found herself stripped of everything during two of the most turbulent time periods in the history of China, she never stopped having a strong work ethic and will to survive.

Tai Tai was born in 1914 in Yangzhou. Back then, daughters were considered worthless compared to sons. Tai Tai was lucky enough to live at birth. She grew up without either of her parents. Her mother died of illness when she was seven; her father, unwilling to raise two daughters, kept her infant sister but sent Tai Tai to live with her wealthy uncle in Nanjing. There, she worked alongside other house servants.

Before she died, Tai Tai’s mother told her, “You must be a hard worker. Never be lazy. One can die by disease, but not by diligence.” Tai Tai’s life coincided with unfortunate historical periods – the Japanese invasion of China upended her life, the Communists stripped her of everything once again, and her gender limited her. With a turbulent life ridden with conflict, Tai Tai never accumulated wealth or lived the lives they deserved.

Yet through it all, Tai Tai stayed diligent. She worked hard to live and lived to work hard. Tai Tai told her difficult past to motivate my mother, who passed it down to inspire me. Here is Lu Lanying’s story. (The following interview has been translated from Mandarin to English, edited, and condensed.)

Q: Tell me about Tai Tai’s childhood in her uncle’s home.

A: Tai Tai’s uncle worked in the pork industry. His company was Nanjing’s biggest one. His house had over 100 servants, so he was extremely wealthy. Because Tai Tai was such a hard worker, her uncle eventually refused to have her cook and clean in the kitchens. He taught her how to manage the business’s profits. At 11, Tai Tai became an accountant. Although Tai Tai never had an education, she knew how to count, and became very good at it. Every day, she counted money from a leather suitcase her uncle gave her. When she got married at 17, Tai Tai told me herself, her uncle gave her a huge wagon-full of dowry to show his appreciation for her contributions.

Q: How did the Japanese invasion change Tai Tai’s life?

A: When the Japanese invaded China in the 1930s, Tai Tai and her husband’s business collapsed. They had to flee to the countryside because the Japanese targeted the cities. Remember the Nanjing Massacre? All they could bring was clothes, jewelry, gold, and silver. Initially, Tai Tai wanted to flee back to her uncle’s house and escape to the countryside with her uncle, but her husband refused, saying “No, you have to come with me.” So Tai Tai obeyed, because that’s what wives had to do.

It turned out to be a huge mistake. Tai Tai’s husband unknowingly led the family into an area infested with gangs of bandits and outlaws. They robbed them of nearly all their belongings, except for their children. At the time, Tai Tai’s daughter was only 3 years old, and her son still couldn’t walk. Empty-handed, they kept traveling to the countryside, staying overnight in other people’s homes. At one point, Tai Tai fell gravely ill. She thought, “I might as well die, I have nothing left.” Yet her strength pushed her to survive. She and her family went on to live in the countryside for years until the Japanese left Nanjing.

Q: What did women’s rights look like during that time and how did it impact Tai Tai?

A: During the Old Society, women didn’t have many freedoms, in politics and in marriage. If Tai Tai didn’t have to listen to her husband and went to her uncle’s place, they wouldn’t have encountered the bandits. In Tai Tai’s early years, if she wasn’t a girl, she wouldn’t have been sent to another home.

During the New society, women had more freedom. For example, women could have respected opinions. Living in one of China’s biggest cities, Tai Tai was considered a “new woman,” so thankfully, she didn’t bind her feet unlike the women in China’s rural areas. Even in her hardships, Tai Tai was capable, independent, and smart, exceeding societal expectations for women.

Q: What life lessons did Tai Tai teach you that you still remember?

A: Never be lazy, always work hard. She always told me, “Don’t let the oil bottle fall over and do nothing, even in the most difficult times.”