Evolutions has its name for very specific reasons. It assists the evolving minds of its students, but it is also a constantly shifting entity in itself — a first year program that has combined educational disciplines in ways Wellesley has never previously seen, successfully and unsuccessfully. The name ‘Evolutions’ encompasses the successes and the failures, the shifts and fixtures of this fledgeling venture. The year has brought highs and lows, but in the end, Evolutions will persist. And it will evolve.

The Evolutions program had been in the works for a long time. Dr. Jamie Chisum, principal at the high school, pitched the idea himself after seeing similar programs at Concord-Carlisle and Brookline, and worked tirelessly with numerous staff members for roughly a year to plan out the implementation and execution of Evolutions. English teacher Mr. Thomas Henes, History teacher Ms. Emily Shapero, Math teacher Mr. Craig Brown, Science teacher Mr. Laurence Lovett, and Art teacher Mr. Brian Corey combined to teach and lead the 80-student program this year, cycling thoroughly through various interdisciplinary and collaborative units, including Time, Space, Man & the Machine, People, and War & Peace.

Origins

So how did Evolutions begin? How did this program go from a concept to a reality? These questions begin, first and foremost, with Chisum.

After seeing the interdisciplinary programs at Concord-Carlisle and Brookline, Chisum knew he wanted to bring this different style of learning to the high school. “I had a group of about 20 or so teachers that I had talked this up to,” he said. “And we started to plan. What would we do? We started to pull together a team and just planned for about a year. No program, just teachers.”

“We did the budget ask [for the Evolutions program] my first year as principal, and school committee supported it,” said Chisum. “They were tremendous. I’m really humbled that they believed in me, and in this vision, enough to support it.”

The five core teachers and Chisum worked relentlessly over the summer to shape their curriculum. However, it did not necessarily go as expected.

“I think I envisioned [the curriculum] coming together much more quickly,” said Henes. “We had these ideas about being interdisciplinary and teaching together, students being able to move between disciplines really easily, and then being flexible with it, and I think especially at the beginning we found that it’s just not that easy to change the way we approach that. It takes a lot of work, a lot of time and planning, and it’s really about changing the culture, which we have succeeded in in some ways and in some ways we haven’t.”

Ben Burns ’17 echoed that sentiment. “The teachers in evolutions did an exceptional job of starting up the program from scratch without a set layout,” he said. “[but] they could’ve done a better job of guiding students into being completely independent learners.”

“I think it took a lot of our students time to get comfortable with the flexibility and freedom in the program,” said Shapero. “Something we can definitely get better at is treating self-directed learning as a skill that students build over time. This year on our first project we told the students they could do whatever they wanted — and for a lot of them that was totally daunting and overwhelming.”

Outsider vs. Insider Perspective

As the year built, and Evolutions students and teachers grew more and more comfortable with themselves and with each other, themes started to emerge. The students’ learning become more and more independent and focused, and the teachers became increasingly able to guide the large group, but stigmas around the program also materialized.

“I think one really big misconception around the building is that our students don’t work as hard as students in other classes,” said Shapero. “It’s a very different experience to follow a set of instructions and end up with a specific end product than to be told that you have to conceptualize the product, design the steps, and do the research. When you look at an end product from one of our students, it’s almost as if the student has done all the work that teacher does in building an assignment too.”

This, to the teachers, is the crux of what outsiders do not understand about Evolutions: it is simply different. Project-based learning is a different animal, with different expectations and different concepts.

“When you look at the Capstone projects, do you see the product or the process?” Brown asked. “You see the product. As a math teacher for many years, I only formally evaluated students on their products. It was ‘can you get these questions right or wrong?’. We are so product-driven in my regular classes because formally, we thought that was the best way for kids to get the best process.”

“This year has been very eye-opening to me,” said Brown. “Because it shows that great learning is fantastic no matter what it is. Good products usually mean good process, but mediocre products can still mean excellent process.”

Corey agreed, saying: “One skill students need to come to grips with quickly in the Evolutions program is how to fail with grace. I think that is a really hard skill set for individuals at the high school to learn and to wrap their heads around.”

First-year Challenges

The thing is, challenges did come up. Frequently. Tiger Mar ’16 said that his greatest challenge in Evolutions was adjusting to the amount of group work the program included.

“The most difficult thing I experienced was learning to work with greater, more diverse groups of people for longer periods of time,” said Mar. “I used to be the person who would either take hold of the entire project or step back and let others do the whole thing, but Evolutions taught me those essential collaborative skills that are crucial to working anywhere outside of high school.”

The group work in particular stood out to the teachers as a particular difficulty for parts of the year. “Something that is totally different with Evolutions compared to other classes is that we ask students to work exclusively on a project for an extended period of time,” said Shapero. “And maintaining that interest and energy is a whole new exhausting skill that they have to work through.”

Adding to the list of difficulties this young venture produced were the grading systems. Simply put, the grading did not work.

“This year, we have failed in the grading and feedback,” said Henes. “We were so busy prepping, making experiences, and getting them through the process that that other side of assessments and feedback was totally one of our weak points. One of our goals for next year is to eliminate the adversarial teacher-student relationship in grading while still giving positive and helpful feedback. What is exemplary? What is proficient? We are trying to figure that out.”

This goes back to Corey’s point: students in Evolutions have learned to fail with grace. Beyond the basic concept of interdisciplinary learning, beyond the group work and the community-building, the main tenet of Evolutions seems to be adjusting to failure while still learning.

“Is it all flawless work?” Shapero asked, referring to the hundreds of student-produced projects Evolutions has spawned. “Of course not, but that is just as important to the program — failing forward.”

“Failure isn’t an F in Evolutions,” Corey repeated.

“This isn’t testing,” added Lovett. “This is project-based. And I think it’s something that will be seen a lot more in schools. It’s a really good way to show your knowledge.”

A Different Way to Learn

For better or for worse, the projects the students create will be the legacy of Evolutions. The projects are the physical representations of the work the students and teachers put in, the learning the students obtain, and the view outsiders will receive. This year, predictably, the projects were a mixed bag.

“A lot of the projects are posters that just present data,” said Lovett. “And that’s not a bad thing. It’s like IRP. I think the good thing is that a lot of the projects weren’t just data. Being the engineering and science teacher, I would like to see more of the built stuff. I think the difference [between Evolutions and IRP] is not that we have posters and that’s bad, it’s that we also don’t have posters and that’s good.”

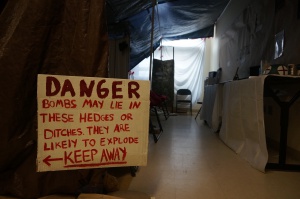

One of the most spectacular projects produced a bench that memorialized numerous war veteran alumni and staff of the high school. Others included students building stirling engines and aquaponic systems, writing short stories, filming documentaries, coding video games, researching the psychology of adolescent development, traveling to Nantucket to collect data on beach erosion, and redesigning urban neighborhoods.

“I always thought the only way a student could show their intelligence was to so by following the outdated and rigorous learning style of the high school,” said Burns. “However, this year I discovered the style of learning Evolutions offers can be an alternate route of showing a student’s academic worth.”

However, not all of the projects were great, and the teachers fully admit that. “I think the expectation with Evolutions is that it is project-based learning, so all of the students will churn out these amazing projects,” said Henes. “Once we understand how to guide students down that road, we might be able to get there, but every year is a brand-new year, and we can’t expect it to be the best set of projects ever. Our first Expo was the first Expo.”

The project-based and student-focused curriculum, while producing projects of varying impressiveness, gave students the freedom to pursue their interests while also engaging with material that they would not have otherwise considered.

“Evolutions has altered the way I look at how I learn, and more importantly, how those around me learn,” said Caroline Lane ’17. “I’m interested in education as something to study in college, and Evolutions has been a great way for me to learn about a different approach to teaching.”

This different approach is just as clear to the teachers as it is to the students. “One thing people don’t understand about Evolutions is that [the teachers] learn as much as the students do,” said Shapero. “We have kids picking projects on a range of topics, and not only am I learning about those topics, I’m learning about the process of researching those topics.”

A New Community

The everyday closeness in the teacher-student relationship in Evolutions is basically unprecedented at the high school, especially given the 16:1 student-teacher ratio with the five core teachers. This sense of community, which they have built through regular program-wide meetings, team-building sessions, and off-campus field trips, has made the daunting first-year venture much, much easier for kid and adult alike.

“I feel less like an authority figure this year,” said Shapero. “You are not just standing in front of a room giving directions. When I work on a project with a student, it isn’t me helping them. We figure it out together. It is a collaborative relationship.”

“It’s four hours a day as opposed to four 59 minute periods,” said Henes. “We see them as human beings and they see us as human beings, for all of our glory and all of our pimples and scars.”

The students agreed wholeheartedly, citing the relationships they built as the most memorable part of the Evolutions experience. “[The teachers] allowed us to develop relationships with them both academically and personally,” said Lane. “They were not only invested in as us students, but as people as well.”

However, it was not just the student-teacher experience that was different. The way the juniors and seniors interacted truly surprised many involved in the program. “The greatest experience [in Evolutions] was continuous throughout the entire year, and that was breaking down the barrier between juniors and seniors in the program,” said Mar. “Within the first few weeks, I became completely blind to that division, and that was honestly the single most liberating thing I have experienced in my entire high school career.”

“I feel like forming relationships with students is the best way to help kids learn,” said Brown. “Those relationships are why I became a teacher. Through Evolutions, I have formed more relationships with students then in any other school year.”

The Negative Perception

This sense of community just makes it that much more confounding to the members of Evolutions when people outside of the program attack the learning style. Students around the school have questioned the amount of work Evolutions students put in, and the most vigorous complaint has been around the fact that Evolutions students receive honors credit for the course on their GPA.

“It reads like resentment,” said Shapero. “I would ask students to be introspective about why they feel that way. Personally, the negative reactions from other students in the building has been very hard for me to hear because I see the impact it has on our current students in the program – they have really put themselves out there to learn in a new way, and sometimes it can be really hard on them to constantly hear this feedback from their friends and peers.”

“It’s easy to criticize from the outside, when you haven’t done it already,” said Brown. “And if you had the option to do it, but chose not to do it, you shouldn’t be upset with the people who did, but rather ask yourself why you didn’t.”

This is the paradox of every anti-Evolutions argument. If a student wanted to take Evolutions before this year, they certainly could have, or they could take it in the future. If students argue that Evolutions students don’t work hard enough, well, they could have had that same workload. If they say that receiving honors credit is unfair? They could be taking Evolutions and receiving that same honors credit.

“There are some people who will never like it,” Chisum said. “And they shouldn’t be in it. That’s my answer to them. And it’s okay. Just let it exist for the kids who do love it.”

“We wish those who react negatively took some time to genuinely understand just how much the students who are really giving it their all are learning about the academic disciplines, about collaboration, and about life-skills,” said Shapero.

“I think Wellesley tends to be a more conservative place, adults especially,” said Chisum. “I think adults fear that because the students in Evolutions are getting honors credit, it puts their kids at a disadvantage. But I don’t see how it hurts the kids. We don’t rank here. A rising tide raises all boats, and we all do better when some of us do better.”

What Will Change?

Despite the sentiments of those involved with Evolutions, this outside stigma, combined with the positive and negative experiences of the first year, has led to some sizable changes in store for next year’s program. Evolutions will only have about 20-25 students in the program next year, they will have 2.5 color blocks free as opposed to the 1.5 free they had this year, and the teachers will be adjusting the curriculum. This, unfortunately, means Brown will no longer be teaching in the Evolutions program and will transition back to ‘regular’ math.

Brown, however, sees this change as a potential positive. “I want to open up channels between at least the math department and other departments,” he said. “Or help negotiate with other departments to have some sort of interdisciplinary activities. I’ve had some teachers talk to me already about what they want me to help facilitate.”

The most visible shift apart from the lack of math in the curriculum will be the amount of time spent out of school. This year, the program went on many different field trips across Wellesley and beyond in order to add a real-life perspective to the learning, but the schedule for next year may conflict with that. “More color blocks out of the program might restrict when and where we can go on trips,” said Henes. “We will have to look more within the local community to enhance our out of the building learning.”

The nearly 60-student drop-off in enrollment may also seem alarming. The teachers wanted to to cut the enrollment down to about 50 students, as they felt that 80 kids was simply too large of a program, but the relative lack of interest surprised them.

“What are we not doing?” asked Chisum. “We have got to figure that out. The teachers worked really hard this year. I don’t think this is a judgement on them. But we have to look at what the kids in the program are saying needs to be done to improve the program and we need to listen to them.

“I believe in what’s called the ‘implementation dip’,” said Chisum. “You start and everyone’s excited, and you get rolling along, and then it gets hard, because it is hard work. Education is not easy, and teaching kids is difficult. So we have clearly hit a dip. Now what do we do?”

“The dip is good,” Chisum continued. “It cuts us to the bone. We’ve cut back as far as I am willing to cut back. If we had eight kids in the program, I wouldn’t run it. But think of how much better you are in the second year of doing something than in the first year of doing something. How much do these teachers know about collaborating, about working across disciplines with kids in this open format, that they didn’t know last year? What would they do differently? A million things. Now they get the chance to go do it.”

The teachers have already begun to incorporate student criticisms into their plans for next year. They know that they have to both polish what they have done well while simultaneously improving and adjusting elements of Evolutions that they feel lacked consistency.

“Another concern that we are aware of is the inconsistency of “academic rigor” at times within the program and between our individual teacher approaches,” said Henes. “We hope that as we continue to work together as a teacher team, we can help each other get to a consistency that students find challenging yet appropriate.”

“[Our] goals for next year are: building our community partnerships to have projects and learning that are grounded in authentic, real world issues and applications; improving our ability to give meaningful feedback to our students so that they can take more personal responsibility for their progress, and finding ways to share what we are doing with the school and larger community,” Henes continued.

The fact that those involved agree on almost unanimously is that Evolutions has a place in the high school. Project-based and collaborative learning is not just a new trend in education. It is persistent, and it is necessary. It offers a unique opportunity to the students that do not enjoy ‘regular’ classes. For what is really the first time in the history of the high school, kids can decide what they want to learn, and they will actually learn about it.

“Experiential, project-based, and collaborative learning is going to become standard practice around the country,” said Shapero. “WHS is a top school, and to stay that way we have to be at the front-line of innovative teaching and learning – that means keeping Evolutions, and keeping a lot of the really impressive work that our teachers already do in their more-traditional classes. I hope that we can expand the program back up to about 50 students and that it is a place where students who have a deep-seated natural curiosity about the world can flourish.”

“Student stress is really high here,” said Chisum. “Parent stress is really high here. We created it. And if you create something, you can un-create it. We have that power. Are we willing to do it? There are things we can’t control, for sure. Can I control what colleges tell you you have to do? No, I can’t control that. But we can control what we want to do with our lives. We can control what we want to do with our schools.”