A version of this article appeared on print in our November 2016 issue.

“It made the hair on the back of my neck stand up,” said Wellesley school Superintendent Dr. David Lussier. “I had never seen anything like it,” added high school Principal Dr. Jamie Chisum.

On the evening of July 14, a Wellesley student posted a series of screenshots from a private group chat to Facebook. Seven male students, three of whom attend Wellesley High School, sent the chat virulently racist messages about their peers as well as messages referencing homophobia and genocide.

Commenters were shocked by the extreme degree of the messages. Many had never seen such overt and unapologetic racism. As included in a report from NECN, messages included on that read, “I’m fed up with this s***/ N****** taking our jobs”. Another student sent “You f****** hate n***** right?/ Cause I don’t know about you but I’m trying to genocide their a**”. A third message said “If one more f****** n***** shows up in this chat I’ll lynch him”.

While the poster received praise for his actions exposing the brutal racism, the post did stir up controversy. Comments on his post also condemned the students who sent the hateful messages and devolved into death threats towards them. Thus, the post was soon removed from Facebook.

School authorities soon took notice as well. The school’s disciplinary actions must remain confidential, however, due to the age of the perpetrators. However, Chisum explained that each student received a disciplinary hearing from the school administration to explain his side and the administration penalized the students accordingly. “I just wanted to know why. I wanted to know how it happened,” said Chisum regarding his conversations with the students.

Lussier said that, despite his initial reaction of outright anger, he believes throwing the book at students is often uncalled for. “You want [discipline] to be done in a way that feels restorative,” said Lussier. “Regardless of how bad the mistake, you want kids to be able to recover and learn from it.”

“No one contended that they did it. They all admitted that they did it…. [The offending students] really showed contrition,” said Chisum. According to Chisum, two of the students’ families contacted him before he even reached out to them.

The police also became involved, but, again, due to the status of the offenders as minors, the extent of any charges remains confidential. As Lussier pointed out, the police will only charge offenders if they deem their actions to be criminal in nature.

The response to this hate spanned beyond the walls of the school and shook the community as a whole. “The community was hurt by it. It became about more than just these conversations, these postings. They woke people up,” said Chisum. “What you hear after that is all the different pains that people have felt here, particularly people of color, about how difficult it is to be a person of color in the town of Wellesley, not just Wellesley High School.”

For World of Wellesley (WOW) president Michelle Chalmers, reading these messages warranted immediate action. “When you are feeling this trauma, you have to be heard. You want people around you,” she said. Feeling this, she immediately organized a town gathering.

At the event, 80 people attended and stood in a circle, singing and speaking about race and diversity. After this small gathering, WOW organized a second solidarity potluck on the town hall law before the first day of public school. Over 400 attended this event. Tendai Musikavanhu, the father of one of the families targeted, and his son Bobo Musikavanhu spoke at the picnic about the importance of forgiveness in a situation where feeling anger would be far easier.

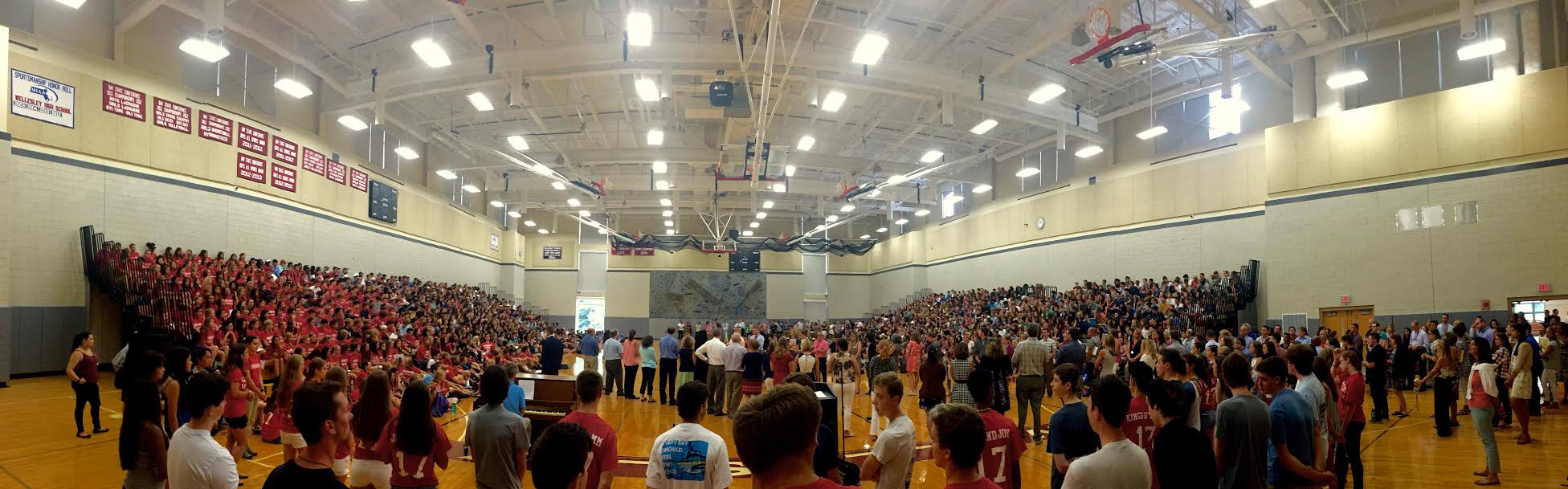

Chisum spoke to all students at the school’s opening assembly. He wanted to convey the overwhelming feelings of the faculty — that these actions and words were inexcusable and intolerable. “The message I wanted to send is that [racism] is not OK — we’re not OK with it; we’re outraged by it. We are upset. We are not just sad; We are angry. We are frustrated by it. It’s not just something we are going to condone — in any way,” he said.

Chisum also outlined his visions for the way the school will address race and racism as the school year progresses. One of the key components of his vision is the newly created One Wellesley. The group, for which there is a teacher component and a student component, aims to build positive, constructive discourse around the topic of race in Wellesley.

The district also aims to prioritize hiring faculty of color. Lussier emphasized how important it is to have a diverse staff. Not only is it important for students of color to have a teachers who looks like them, but it is also important for all students to learn from teachers of varying backgrounds, races, and perspectives. For the 2015-2016 school year, 10% of new district faculty identified as people of color. For the 2016-2017 school year, that figure rose to 20%. Lussier hopes this percentage will continue to increase.

Additionally, district-wide, staff will receive thorough training on addressing race in school and facilitating discussions around racial issues. “We are looking at our curriculum to think about enhancing the ways in which we embed conversations about race and diversity,” Lussier said.

The entire district, K-12, will also undergo a comprehensive curriculum review to evaluate how each school and each grade level confronts topics of race and diversity — whether it be the Ghana unit in first grade or reading Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in eighth. This will be the first time that the district has launched a full K-12 curriculum review.

Lussier explained that the review not only moves to catalyze inclusive discussions in the classroom but also to silence the idea that microaggressions in Wellesley are isolated. “We are moving to do a formal assessment on the climate of race and diversity in the district,” he said. “Not just to have a baseline but also to point to other people who might want to hide this under the rug and say ‘no, this is bigger than just an incident on social media or a couple of folks coming forward; this is actually a part of the culture that we have to have the courage to acknowledge and to address.’”

Chisum hopes that from this, the district will craft a unified curriculum that fairly represents diverse perspectives. He does acknowledge, however, that this type of systemic change will not occur overnight.

“I want people to understand we are not going to stop talking about [racism],” said Chisum. “Hopefully, with kids’ help, with teachers’ help, we talk about it in relevant, meaningful ways. I’m acutely aware that I can’t keep lecturing people and have it be effective. We have to find and continue to find relevant, authentic ways to have a conversation.”

Lussier added that he hopes these changes will have profound impacts, and that Wellesley’s reactions to racism will outlast the racism itself. “I don’t think any of these things are unique to Wellesley,” he said. “I think what sets us apart is how quickly the community comes together in one voice to say ‘no, this is not who we are.’”