Over the past few years, school attendance rates have been steadily declining in Wellesley and the nation. More students are missing class while most attendance policies have remained relatively unchanged. This change may indicate a shift in attitudes regarding the role of in-person teaching versus digital learning, bringing into question the importance of attendance in our grading and credit system, and casting doubt on the very foundation of the purpose of school.

Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic absences in schools have been rising in the state and nationwide. The Department of Education defines chronic absenteeism as missing at least 15 days of school — or around 8 percent of the school year—for any reason, whether excused, unexcused, or suspended. For many states, including MA, chronically absent students are students who miss at least 10 percent of the school year. Being chronically absent can negatively impact a student’s academic performance and even prevent them from graduating on time.

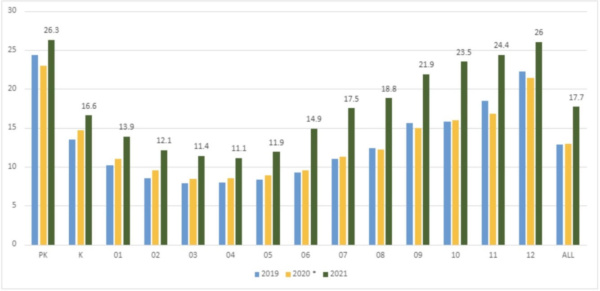

Across the nation, between the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, the percentage of all students considered chronically absent grew from 19.7 percent to 28.9 percent. According to the state Department of Education, for MA students in grades 9-12 during 2021, that rate was an average of 24 percent. As reported by Boston.com, the rate of chronically absent students school year from 2018-19, before the pandemic.

But what about attendance rates at the high school?

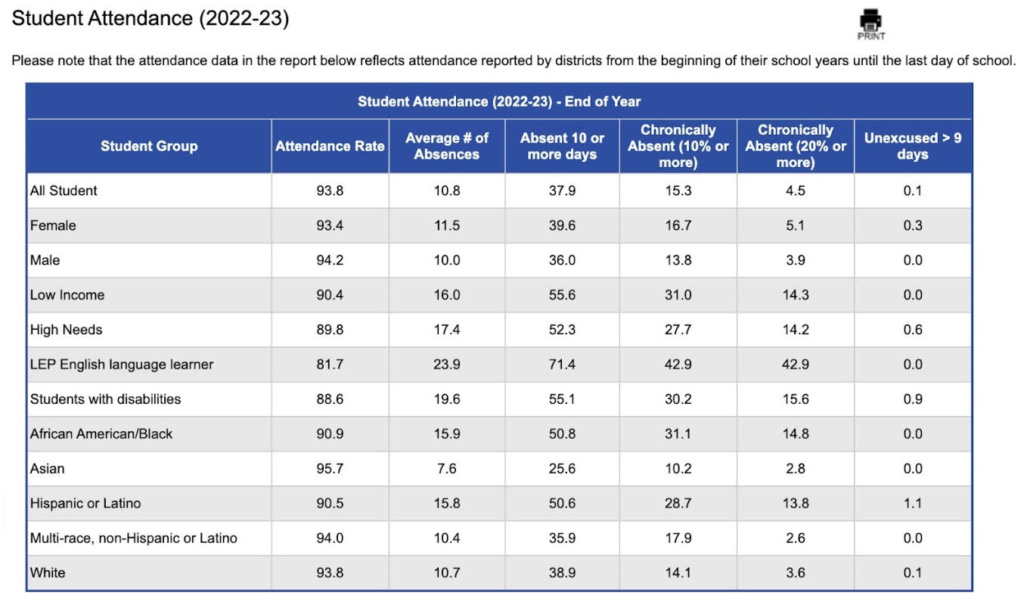

During the 2021-22 school year, the high school’s attendance rates recorded in the Department of Elementry and Secondary Education showed that the average number of absences each day was 9.3, 36.0 percent of all students were absent 10 or more days, and 11.0 percent were chronically absent (missing at least 10 percent of the school year).

In the 2022-23 school year, the average number of absences was 10.8, 37.9 percent of all students were absent 10 or more days, and 15.3 percent were chronically absent— the numbers had increased across the board.

The attendance rates for the high school during the 2022-23 school year have also risen, with nearly one in every seven students considered chronically absent (defined as having missed 10 percent or more of the school year). Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Department of Education.

“During the pandemic, more and more students got used to this notion of online,” said Dr. John Steere, school counselor for Perrin House. “In getting back to [the] everyday routine of school, teachers and administrators have had to be stronger with saying, ‘You are expected to be in class.’”

However, the high school’s on-paper attendance policy, which has remained the same for the past eight years, addresses chronic absenteeism more leniently.

In the high school’s Student Handbook, students receive an ‘N’ grade (meaning no grade and no credit computed) if they miss 11 class periods in a quarter, nearly 25 percent of the total number of times that class meets. For Term four seniors, due to their shorter last quarter, that limit is reduced to six class absences in the quarter, excused or unexcused. If any student receives 1 ‘N’ in a year-long course, 25 percent of the credit will be reduced. If the course is semester-long, 50 percent of the credit will be reduced. Depending on the number of ‘N’ grades received, the student may lose enough credits to fall short of the 136-credit graduation requirement, thus being unable to graduate.

Although the major determinant for student graduation is completion of that 136-credit requirement, non-completion is very rare, giving students considerable leeway.

“When your attendance starts to be poor, it starts to affect the credits,” Steere said. “But many WHS students finish well above 136, so even if they got docked 1.5 or three credits, it’s not going to affect them as much.”

Such leeway could incentivize students to skip class. If a student misses twenty days in a school year yet still graduates with the same amount of credit earned (albeit with a lesser grade) as a student who has near-perfect attendance, then the purpose of actually going to school is diminished which is not what the school administration wants.

“You can fail for a quarter, but end up with 6 credits for a year if the year-end grade averages out to be above a failing grade,” said Mr. Collin Shattuck, assistant principal of the high school. “We need to think about how our policies might be attributing to this chronic absenteeism.”

However, this leniency in the high school’s attendance and grading policies also provides support for students who face serious reasons for being absent and are doing what they can to keep up with the work.

“We have the flexibility to make the consideration that [such students] really earned the credit by doing the work they missed while they were out,” Shattuck said. “We don’t want to penalize [students] for absences out of their control, so there’s a little bit of flexibility and compassion that we can show while holding a certain standard.”

The Student Handbook’s language creates further flexibility when enforcing attendance. Students can avoid ‘N’ grades if “there are extenuating circumstances presented to the student’s Assistant Principal.” But even if a student receives an ‘N’ grade, the question of how “credit” is earned remains.

The high school’s dependence on digital teaching tools such as Canvas and the growth of artificial intelligence in education such as ChatGPT may especially perpetuate this issue.

“How do we find the happy median between students getting the information [through these online resources] but also getting the relationship by being in class?” said Steere.

According to Shattuck, credits should also be determined by time spent on learning in class, not solely by the work turned in or assignments completed through Canvas. Students’ presence in the classroom should factor into grading to provide incentives for improving attendance. Teachers should also have the discretion to decide how and which assignments should influence credits, as long as arrangements are uniform for all students.

With the high school’s increased use of online platforms such as Canvas over the recent years and the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) in education such as ChatGPT, students feel less obligated to attend class in-person when they can merely turn in assignments remotely to earn credit.

“I felt that if I stayed home, I would be able to use my time more productively to get caught up on work because when I was going to school each day, I would be so tired by the end of the day that I wouldn’t get any work done,” said Charlotte Elwy ’24.

From the student’s perspective, returning to in-person schooling also means facing the stress of heavier workloads and fuller curriculums—other contributing factors to chronic absenteeism. Students’ mental health becomes a critical issue to consider, especially in the context of the high school’s high academic standards for students.

“I think the WHS culture of academic excellence can be suffocating and force students to feel like they have to spend entire days pushing through work at home instead of being present in class and engaging with course content,” said Elwy.

For some students, absenteeism may be acceptable to a certain extent depending on the types of classes being missed, such as math classes versus foreign language classes.

“There’s a difference between skipping a class that you can self-teach yourself in and one where you really need assistance from the teachers,” said Daniel Zhou ’24.

According to Zhou, generally speaking, students should not be able to stay at home at their leisure to catch up on late work at the cost of missing in-class time.

“I think people should be able to manage their work unless they’re taking a lot of hard courses. I feel like you should be on top of your work most of the time,” said Zhou. “I try to minimize my absences because I don’t want to miss out on class and get more behind.”

Similarly, administrators believe that students should still acknowledge the value of in-class time.

“The real crux of teaching happens in the classroom,” said Steere. “We want students to actually experience being in class so that they don’t miss the small things. If you’re going to have questions, if you’re going to figure stuff out to make sure you’re doing it completely right, you’re going to want to be in class.”

If the systemic goal is to complete all given work on time to earn credit, in-class time may become a barrier for some students.

“I definitely think in-person classes are more enriching and valuable for students because of the ability to form interpersonal connections, but the action of physically being in school for seven hours can be exhausting and make completing work even more difficult,” said Elwy.

The relative leniency of the high school’s attendance policies was designed with the intention of helping students.

“[This policy] was actually in an effort to try to help students who were dealing with the difficulties of going to class—not cutting class, but illness, physical ailments, or other health issues. It was actually intended to help students,” said Steere.

The administration may regard creating flexibility for students as an attribute to worse absenteeism. But students may feel otherwise. It’s necessary that the high school’s approach to attendance creates more benefit than cost for its students, but currently it seems to be more double-edged.

The administration designed these attendance policies with the goal of getting the students into class. But is this goal actually helping students? The increasingly prevalent question of whether work done remotely counts as credit-worthy “learning” and whether in-class time provides efficiency for students remains unanswered.

To strike a healthy balance between work done in class and at home for students, should there be adjustments made to our current lenient attendance policy? Should the determinants of earned credits be more explicit, placing more emphasis on in-class presence to more effectively curb absenteeism? If our teacher policy includes focus on maximizing in-class productivity to minimize homework, would that improve student mental health and reduce potential absenteeism? How can our policies provide accessible teaching such that students won’t turn to advancing technology for help?

Administrators and students will—and should—continue to ask these questions going forward, especially as times continue to change. Ultimately, transparency in communication remains critical for students and administrators regarding absenteeism. Students should call in as many of their absences as possible. Simultaneously, the administration should inform students of attendance requirements so more students—especially those who don’t usually check the Handbook—are aware.

“Absences can happen for a number of reasons, kids can miss assignments for a number of reasons,” said Shattuck. “That’s why our house team has to know what’s going on so we can figure out what the most fair policy is.”