“I shouldn’t have to write about this.”

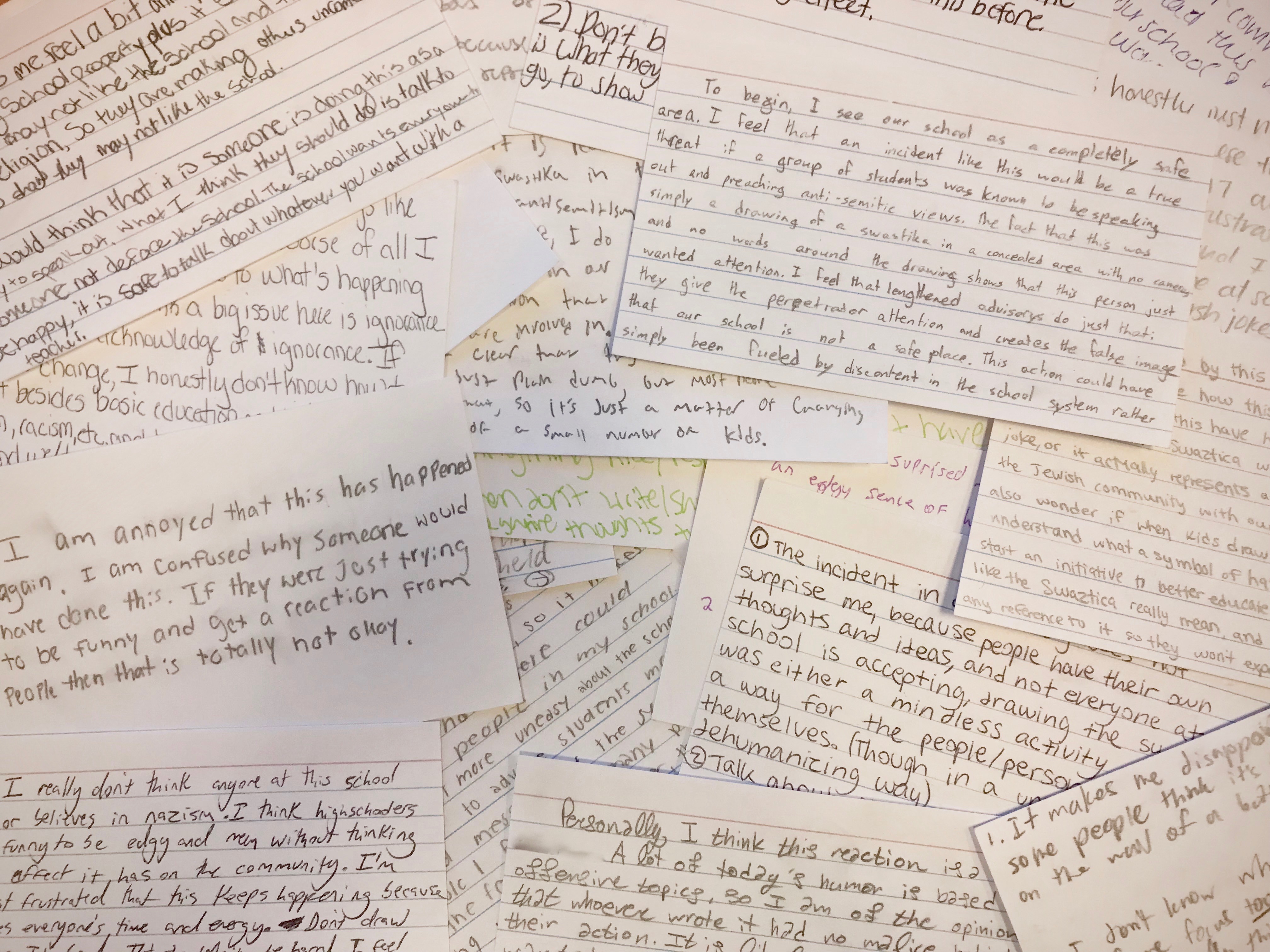

That was my initial reaction to hearing the news on a Friday night two weeks ago, when principal Dr. Jamie Chisum wrote a somber email to families and faculty reporting that a student at the high school had drawn a swastika in a boys’ bathroom stall on the fourth floor.

Being Jewish, I have felt angry, confused, and ultimately disappointed that communities in the United States, especially Wellesley, are still confronted with symbols and acts of anti-Semitism. At the same time, I believe that this current controversy the community faces provides us with the opportunity to reevaluate the effectiveness of how students learn about and understand the Holocaust and history of anti-Semitism.

From my experiences at the high school, I find the school community at its core to be welcoming, accepting, and not anti-Semitic. However, some people seem to lack a true understanding of the impact of what they perceive to be harmless jokes about Jews, the Holocaust, and yes, even the defacing of school property by drawing a swastika on the wall.

We may never know what motivated the perpetrator. I have heard some students comment that they thought it was likely that the swastika was drawn to be “funny” and was not based on any real malice or anti-Semitic beliefs. Perhaps, people theorize somebody thought they were being “edgy.”

Whether or not this is the case, and understanding that the true motive of whoever drew the swastika is unknown, the administration’s response and actions against that student need to reflect the gravity of the act, regardless of the motive behind it.

In a school that preaches tolerance but still faces undoubtedly offensive acts from its students (both subtle and overt), calling for an extended advisory period to talk about the incident and/or an announcement from the administration will change very little. Instead, students and faculty must examine the crime (and it is, in fact, a crime) more thoughtfully and critically at a fundamental level, including the manner in which teachers educate students on the Holocaust.

A symbol of this magnitude should never be reclaimed, made mainstream, or be used for any other meaning that differed from what the Nazis stood for nearly 80 years ago. The swastika represents the six million Jews in Europe that were stripped from their families and homes to suffer brutal and inhumane tortures and death, simply because they had a certain set of beliefs.

The swastika represents the Nazis that killed nearly 6 million others during the Holocaust including the disabled, Roma and homosexuals. And today, even 80 years later, the swastika continues to represent hate in the forms of anti-Semitism, fascism, and white supremacy. It represents an atrocity committed to the human race so infamous that we vow to never let it happen again.

Yet, the symbol lives on.

So we must ask ourselves, how should our community respond? What is the just punishment for a student that draws a swastika or any other symbol of hate? Should the response be targeted to the perpetrator, if he/she is identified? To the whole student community? Does the student’s motive matter? Does it matter if they are actually anti-Semitic?

In my opinion, the best way to prevent people from sympathizing with and even joking about hate symbols and groups, is to develop their sense of understanding for the victims of hatred through education. It is simply too easy, in an era where so many people feel marginalized by society for a variety of reasons, for people on the edges to find a sense of community by going against the good and decent, instead of working for it.

Students who draw and write such vile symbols and remarks should undergo a thorough in-school suspension that requires education of the atrocities Jews faced before and during World War II, when flags bearing swastikas flew high over war-torn regions of Europe. They should hear the first person accounts of survivors — Jews torn from their homes and families, herded into cattle cars, branded with identification numbers, starved, tortured and left to die. They should look into the eyes of living survivors and be forced to explain their actions. And finally, they should be asked, “Why do you hate?” And the school administration should listen for the answer.

To be fair, the Wellesley Public Schools have been proactive and have made a solid effort to educate students about the Holocaust. In particular, the English and History departments have made extensive efforts to educate their students about the Holocaust, starting in 8th grade with the Facing History and Ourselves curriculum, which provides an in-depth, reflective, and occasionally graphic analysis of the events. Reading Elie Wiesel’s Night in 9th grade, learning about World War II in 10th grade Modern World History, and reading the graphic-novel Maus in 11th grade English, rounds out that content well.

Yet, we still encounter some students acting with hatred. We still hear the subtle, and often not-so-subtle, subtext of intolerance through a Jewish joke, a racist stereotype, and yes, the drawing of a swastika on a bathroom stall.

So, what’s the answer? One answer is introducing the history of the Holocaust to students at even earlier grades, which is a strong first step. The sooner students are exposed to the Holocaust, the more likely they are to develop a true understanding of its appalling nature, to develop not only empathy for its victims, but an understanding of the Jewish community, and the impact of symbols of hate.

While it may seem ambitious, if not unfitting, to advocate for the education and recollection of something as horrific and graphic as the Holocaust, grappling with this difficult time period earlier on in students’ education is necessary for them to positively contribute to a peace-bearing democracy.

With that, Wellesley is not the only town to have witnessed hateful acts of anti-Semitism and racial supremacy in recent times, as these incidents are not isolated. In a time where groups of people have reclaimed the agency to publicly proclaim their hatred towards other races and religions, developing a greater sense of empathy among all Americans is a necessary means to rise above messages of bigotry.