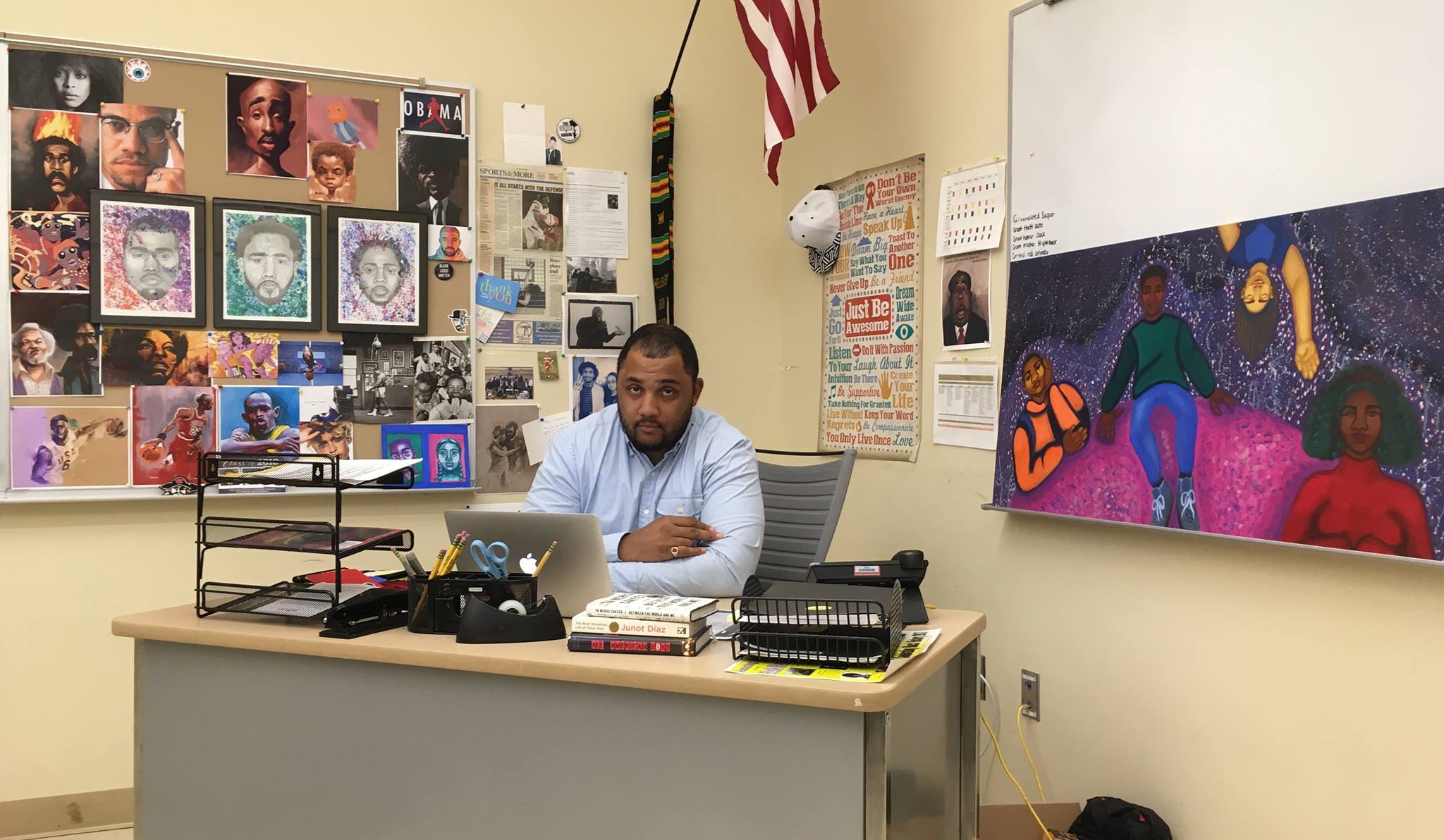

In October 2015, a few tables and chairs, a box of junk, and a coffee mug that read “I love farts” littered the METCO room. Everything has changed now. The room is more orderly, more lively; the mug is absent, replaced instead by pictures and paintings carefully arranged on the walls behind a desk in the far corner, a desk occupied more often than not by the man responsible for the changes, Mr. Grant Hightower.

The changes in the METCO room may be the most physically apparent of all the changes Hightower has created in his one and a half years as METCO coordinator at the high school, but they are far from the only ones. Hightower also co-teaches a wildly popular English class, ‘Diverse American Voices’ (DAV), that doubled its enrollment within a year of its creation; he has been, by all accounts, a diligent and beloved METCO coordinator; he gave the keynote speech at a 2017 World of Wellesley Summit, and, after winning the student vote in a landslide, he was the selection as this year’s faculty graduation speaker.

His varied and numerous accomplishments in just a year and a half made Hightower a logical choice for graduation speaker. Both DAV classes campaigned for his nomination, and according to the class of 2017 officers, Hightower won the vote handily. The class officers tally the senior votes and then select the speaker from amongst the top vote getters. This year, there was no debate; Hightower was the candidate the whole school had wanted from the beginning.

“We all wanted to pick Hightower, and hoped the class would reflect that,” said Satvik Reddy ’17, the class secretary. “Fortunately, he won the vote easily, so we made him the speaker.”

When Hightower first arrived, before teaching DAV, before giving any speeches or getting to know any of his students, the METCO room was really just a space. “That first year I didn’t really put anything up on the wall, but I’ve always been really intrigued with art, particularly student and freelance art, so fortunately for me there were a number of student artists in the school, and they just gave me some of their work,” Hightower said.

The art, as Hightower describes it, changes the complexion of the room. “The art in the room is based around people who I have always looked up to and found inspirational, and who I think the kids should know about but probably don’t,” he said. “I feel like it’s really important, in order to understand where we’re at right now, to understand where we came from.”

Most of the art resides on a bulletin board on the left wall behind Hightower’s desk, with portraits of Tupac Shakur, Nas, Samuel L. Jackson, Erykah Badu, Malcolm X, Richard Pryor, Outkast, Kanye West, J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar, ‘Sanford and Son’, ‘White Men Can’t Jump’, Serena Williams, Lebron James, Michael Jordan, Usain Bolt, and a few others. To the right of the board are pictures of some of Hightower’s students and newspaper clippings with the accomplishments of a few others. To his right is a painting created and donated to him by Mariana Perez ’17, who also contributed many of the portraits on the board. On the far right whiteboard is a picture of Steve Bannon, with the caption: “Wanted for Crimes Against Humanity”.

“Bit by bit, I’ll start populating everything,” said Hightower. “Other than that, the room is just a place where students can take refuge sometimes. I happen to like it when I get all kinds of different kids in here, because I think it’s one of the only rooms that it’s not mandatory to come into. And so I think that kids do get a different experience when they come in here, whether it’s just talking to me, or their peers, or students connected to their peers. I always joke that there’s this symbiotic veil that a lot of white students get, and it’s an easy way to make light of that fear and curiosity. As soon as you step through to the other side of the glass you’ll be fine.”

Hightower’s main responsibilities, as he puts them, are the social, emotional, and academic well-being of the high school’s students of color, particularly from the metro-Boston area. But another one of his charges is lifting that veil that he talks about, bridging the gap between Wellesley resident students and the community of Boston. The speed bumps there are what he always expected.

“The thing with working with teenagers is you have to be reliable,” said Hightower. “But as an adult working with teenagers, it’s my belief that you have to go in with the idea that teenagers are going to consistently be inconsistent. So there’s no sense in setting strict standards. To me, students should come in, at the very bottom line, understanding that the only thing they have to worry about is doing their best every day. And is that going to be hard? Sure. It’s really not impossible, though. It’s when you start taking days off that you start going backwards.”

In the eyes of his boss, Wellesley METCO Director Dr. Kalise Wornum, Hightower could not have been better suited to his role. “I was taught that leadership isn’t natural, that it’s a skill you learn,” said Wornum. “At the same time, there is an intrinsic nature that he has about how to talk and connect with kids. If anyone was born to build a relationship, it’s Hightower. He is authentically true to himself, he is self-deprecating when it’s appropriate, and he is confidence-boosting when that is required.”

For Hightower, his life ever since high school has centered around helping others, mainly kids. In college, he worked in a homeless shelter; after that, he worked in a girls’ home for the sexually abused; from 2009-2013, he worked in the high school’s Special Education department. He then ran four group homes in the West Roxbury area for an organization called Resources for Human Development, which assists the mentally handicapped with their daily lives, until returning to the high school in 2015.

So why helping people? What, for Hightower, made that worth it? First, he said, he’s good at it. But it also fulfills him. He didn’t want to contribute any more to mistreatment. “My belief is the world would [better] operate if we figure out how to work with each other,” he said. “Our connectivity and our collaboration can get us to where we want to be. Is that going to be attainable? I don’t know. I don’t know. What I do know is that my best experiences have been when people from different places who have different experiences, who have different depths of knowledge and perspective, can find a way to work towards a common goal. When there’s synergy, when people who are different can work towards a common end, it’s beautiful.”

Ironically enough, it was a trying school experience that made Hightower originally want to work closely with students. He grew up in a predominantly white town in Connecticut and faced a barrage of racism from students, teachers, and administrators at a very young age. As he recalls it, after he graduated high school he learned that the teachers in his elementary school would keep an open file on the students of color and pass them around to other teachers in the school.

“It was like ‘stay away from this kid’, or ‘watch out for this kid’,” Hightower said. “It was a tracking list. We’re talking about seven, eight, nine-year-olds! And what they were writing about us was some institutionalized garbage projecting what our futures were going to be. And that projection dictated the amount of effort teachers would put into students.”

But being profiled at an early age did not discourage Hightower from wanting to work in schools. A rough high school experience only made him realize that he had an opportunity to help give students the boosts that his high school never gave him.

“I always knew that I wanted to work with kids so they wouldn’t get jammed up,” said Hightower. “I wanted to make sure that they had an opportunity to feel valued, that [during] that 12-18-year-old time frame kids felt important, because to me, they are the ones that can impact the world fresh out of high school, or even in high school. But if you have adults that are just dogging you, for whatever reason, it can stifle kids, make or break kids.”

To this point, Hightower’s METCO students consider him not only a mentor, but a close friend.

“He’s a great person to talk to and I feel like he’s the only person who can embody what it means to be a METCO Coordinator,” said Rashad Halidy ’17. “He’s a great inspiration for the kids in METCO.”

Nykia Lumley ’17 agrees. “It’s like I’m talking to another student in adult form,” she said. “He’s very fun to be around and with him it’s not like awkward talking to an adult. He’s like a friend.”

“Our interactions range from friendly discussions about race to him giving me advice about life in general,” said Zimmie Obiora ’17. “He has made the biggest impact on my time here in Wellesley, and I am extremely thankful that I have the honor of knowing him.”

So far, Hightower has stayed true to his message, not only making students feel valued but challenging and educating them at the same time.

His first foray into teaching a large class came in 2011, when he and another teacher, Mr. Patrick Gallagher, reconfigured and taught the ‘African American History’ curriculum. The class was extremely popular, but Hightower was removed as a teacher after just one year because it became a strictly literary course.

But when Hightower returned in 2015, English department head Mr. John Finneron wanted him to co-teach a similar class, ‘Diverse American Voices’, with Mr. Alan Brazier. Hightower began teaching the class with Brazier in October, as soon as he returned to the high school, and the course has since become one of the most popular senior classes in the school, expanding to two sections this year (with the second section co-taught by Brazier and Ms. Shima Khan) to fill the student demand.

“Everyone was telling me that I would love teaching with him,” said Brazier. “It was pretty extraordinary and I think pretty special because we hit it off — it was just easy from the beginning. There were no growing pains; you know, we were teaching a class together, and that’s really challenging. Teachers can get territorial, and can be control freaks, but for whatever reasons it just worked. And I think that’s because he just brought so much to each class.”

They filled different roles from the beginning: Brazier was more of the traditional English teacher, the moderator, while Hightower pushed kids hard.

“He’s an instigator, in the best sense of the word,” said Brazier. “He’s really good at challenging students to confront their preconceived notions of race and ethnicity. It’s been great to teach with him, because I feel as though I’ve learned a lot from him in that regard.”

Hightower also frequently visited the other section of DAV this year, in doing so building a strong bond with Khan as well. All three teachers planned out many lessons together; often, Hightower would act as a third teacher in the second DAV section. Needless to say, Khan had nothing but praise for him.

“Teaching DAV with Hightower was like trying to play basketball with Jordan himself! I was constantly in awe of his knowledge, his ability to relate to students and successfully challenge them to think outside the box,” said Khan. “Hightower has the special ability to make serious issues relevant to those who probably aren’t affected by them, and he does so with ease. I always like to joke that you go into a conversation with [Hightower] thinking it’s going to be a breeze but then he hits you with the heavy stuff and you don’t even realize that you just got educated beyond belief. His sense of humor, the way he shares his personal experiences, and his dedication and passion to issues of social justice — all make him a star amongst both students of color and our white students.”

Truly, although one may never hear Brazier or Khan say a negative word about Hightower, it is amongst his students — in both DAV classes — that the love for him is most apparent.

“I’ve come to realize that he always knows what to say, and more importantly how to say it, to assure me that things will get better,” said Lily Ameli ’17. “He’s the one person I will miss dearly when I leave for college, and I’m dreading the day I’m going to actually have to leave because I don’t want to lose the sense of safety and comfort that Mr. Hightower has provided me.”

“I remember that after a particularly frustrating class I told him that I was excited to move on to college, where I presumably wouldn’t encounter the same closed-mindedness and insincerity,” said Savitri Fouda ’17. “He sympathized with me, but warned me that moving on from Wellesley would bring a whole new set of racial issues. I largely brushed him off, but a few weeks later I found myself in the METCO room after returning from an overnight college visit, shocked at some of the racial dynamics I had encountered. I was grateful to Mr Hightower for listening to me and giving me advice for how to adjust to college life.”

His students also commonly noted his unique ability to elicit opinions from everyone, no matter their biases. Hightower, those in DAV say, is the rare teacher who often wholeheartedly disagrees with students yet still encourages those students to speak their minds.

“He perfectly handled controversial topics by ensuring that every opinion was valued, and this ensured that people did not hold back their opinions,” said Reddy. “He was also so eloquent, and whenever he gave his input on a topic, the class would be silent because of how impactful his words were.”

“I’ve never had a teacher like him, but I’m so glad I did,” said Obiora. “He came at a time where his unapologetic nature forced everyone to think about themselves and the world around them. He was never afraid to provide insight or challenge an opinion, and always did so respectfully.”

Hightower echoed these statements, saying in his case, he strives to be receptive to the opinions of his students as long as they are willing to stand by what they are saying and back it up with evidence. He may not agree — he often pushes back — but he will listen.

“I don’t think you can have an honest communication if you already think you know where somebody’s coming from,” said Hightower. “You don’t know what somebody’s experience is; you don’t know how long it takes them to come to a realization about what they’re talking about.”

“What [students] see from Hightower is that they can say what they want to say, but whatever side you are arguing, you need to back it up,” said Brazier. “You need to do your homework. And if you haven’t done your homework, if you’re speaking just emotionally, you will know that that’s not enough. You need to combine sharing your feelings and doing your research and reading up before you can form a really defensible argument.”

“It’s easy to throw stuff out there, to say ‘I like this’ or ‘I like that’, to say ‘I align with this value’ or ‘I align with that value’, because what you’re doing, you’re putting yourself underneath this umbrella that you don’t have to hold or be responsible for,” said Hightower. “And that’s easy. But when the umbrella disappears and you’ve decided to put yourself in this spot, now you need to defend that. If a kid can do that, then who am I to tell them that they’re wrong? If they’re wrong because empirically it is wrong, then yeah, we can talk facts. But if we’re talking opinion, if we’re talking emotions and feelings, I don’t know who you are. I don’t understand teachers who think they know everything. Part of this experience of education is learning.”

This year dragged particularly heavy topics — this summer’s racist Facebook messages; rashes of police shootings of unarmed black men; the 2016 presidential election — into the spotlight in DAV, testing the patience and resolve of all three teachers. That learning, for both teachers and students, always came, but there were trying times along the way, particularly in the election’s aftermath.

“I had to be patient,” said Hightower. “I had to be very, very patient. Because to me, there are some things in life that are so obvious there isn’t even need for debate. And this was one of those things. If you’re voting for the dude, you’re voting for some very clear things that you need to own. At the same time, we still have to live here with each other, so I wanted to give kids who felt like he’s their guy a chance to explain what that meant.”

“I think there was a lot of growth, particularly from the kids who supported the current president early,” he continued. “If you stand behind somebody, say ‘That’s my person; that’s my guy’, that’s your choice to stand behind that person. But when you tie yourself to a person you tie yourself to what they do and say, even if that’s not what you would do or say in that position. I think that’s a big lesson that a lot of people have to learn, and I’d rather you all learn it now, when you can make the change and have the energy to learn and try something different.”

Hightower knows that this change takes time, that perspectives do not shift in one class. But opening up students to new perspectives is his goal every year.

“One of the things I say to the parents is my job isn’t to get kids to see the world through my lens, but clean off and develop their lens,” said Hightower. “I don’t think [students] spend a lot of time until that class really thinking about some of these things. It’s the same thing as eating a good dish; we eat food all the time, but how often do we sit there and actually taste the food?”

That clean lens is something Hightower strives to bring to all aspects of his life. He is constantly pushing himself, currently getting his Masters degree at Endicott in organizational management. And while he is an incredibly dedicated teacher, he is an even more devoted husband and father. His wife of almost eight years, Chanelle, is both the architect and the rock of the family; his nine-year-old son, Sevoi, is his humanitarian; his six-year-old daughter, Lydia, his Superwoman; his six-month-old daughter, Solenne, his biggest fan.

“I learn so much from him as a teacher and as a parent,” said Khan. “If you meet his kids, you’d want him to raise your own.”

This lovability and his strong voice elicited a joyous response from students and teachers alike when the class officers announced his appointment as graduation speaker.

“I screamed with excitement when I found out Mr. Hightower was going to be the graduation speaker,” said Ameli. “I had told all my friends to vote for him, even if they had no idea who he was.”

“I think Mr. Hightower is the perfect graduation speaker because he’s honestly just so smart,” said Anand Ghorpadey ’17. “He has a perspective that a lot of kids in this town don’t have, so hearing what he has to say will be very beneficial.”

“It’s about time we had a speaker of color and I can’t think of anyone better suited for the role,” added Khan.

Hightower was not overly emotional about being chosen. He was happy, he said, but above all he felt a responsibility to give a strong and memorable speech. “This particular group has impacted me as well,” said Hightower. “I have a deep love for the class of 2017 — maybe not as much love, but hope. But I feel connected to the class of 2017 in a way that I didn’t expect to.”

That responsibility sticks with him, taking different forms in different situations. When going back to his role as METCO coordinator, he said that he feels he must be representative of excellence in every capacity, not just socially or academically.

“One of the things that I think about a lot is that if I’m the only black person in a position of power that you all run across, am I a good example…of a good adult, of a good man, of a good black man? For me, that’s something that’s on my mind,” said Hightower. “It’s important for me to be the best all the time. It lowers people’s anxiety around folks that look like me.”

He admits that this is hard. He’s 32 and beginning to get gray hairs. It isn’t something he has to do, but he takes it upon himself anyway. And that is taxing. But it will never change who he is, and he will never change to fit someone else’s beliefs.

“When I say put on my best face, I don’t mean make white people comfortable around me,” said Hightower. “What I’m saying is, be the best version of myself every day that I’m here. I’m not dancing for anybody. And that’s the other thing about this speech — I think some people want me to go out there and put on a show. I’m not putting on a show. I think some people are afraid of what might come out of my mouth. That’s great.”

There may be people in the community who are not receptive to what he has to say. But Hightower does not really care. For him, it is all an opportunity to educate, to enact change. Yesterday it was a room; today it is a diversity class. Tomorrow it is a speech.

And he understands wanting to back away, understands being turned off by people who are ignorant, who are not open to change.

“The problem with that,” Hightower said with a smile, “is who is going to teach them if you don’t?”